The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) is working to identify dozens of Black soldiers killed in World War II. They served as part of the 92nd Infantry Division, known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

“The idea that we can first tell them this is how it happened, this is how he died a hero. This is the thing he was doing and what it meant to the war. And then being able to identify him after. It’s just it’s a very, very humbling thing for our job,” DPAA historian-analyst Josh Frank said. “Every story is different.”

In 1866, Congress passed legislation to create six all-Black Army Units. The end of the 19th century also brought the end of the Indian Wars, where the Buffalo Soldiers got their name. Twenty percent of U.S. cavalry troopers were Black. Native Americans referred to them as Buffalo Soldiers to symbolize their respect for the troopers’ bravery and valor.

“The two big units during World War II that everyone talks about as far as segregation goes was the 92nd Infantry Division, the Buffalo Soldiers and the 332nd fighter Group, which were the Tuskegee Airmen,” Frank said.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO LAUNCHED THE FRISBEE, FRED MORRISON, WORLD WAR II COMBAT PILOT AND POW

Members of the 92nd Infantry Division carry guns across a field. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

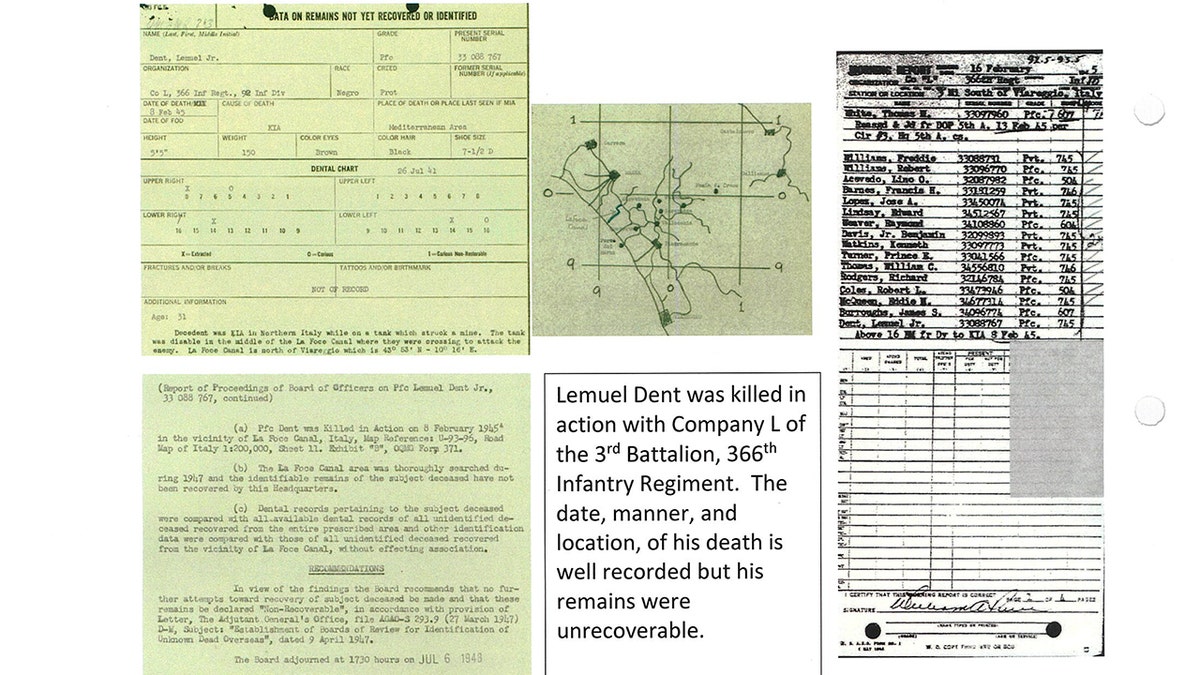

U.S. Private First Class Lemuel Dent Jr. served as part of the Buffalo Soldiers and was recently identified by the DPAA nearly 80 years after his death.

“A lot of people talk about Normandy and Iwo Jima and the Battle of the Bulge. I think the Italian campaign gets a little bit forgotten,” Frank said.

PFC Dent was stationed along the Gothic Line northwest of Pisa, near Viareggio, Italy, along with other members of the 366th Infantry Regiment.

UNCLAIMED NAVY VETERAN TO BE LAID TO REST IN PRESENCE OF COMMUNITY

“There was all this marshland that was between the coastline and the mountains that they were trying to get over,” Frank said. “While they were trying to get past the landmines to get to the mountains, they were getting hit by artillery and mortar fire.”

U.S. Army archive records show documentation of U.S. Private First Class Lemuel Dent Jr., who was killed in World War II. (United States Army 366th Infantry Regiment and other Colored Divisions Collection, #8501. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library)

Dent was riding a tank that came under fire while crossing a canal. The area where he died remained in enemy hands for another two months as fighting continued. It delayed the possibility of recovering his remains and remains of dozens of others.

“The whole 366th Infantry Regiment, which PFC Denton was assigned to, that whole unit was almost decimated,” Frank said.

Thirty were killed in action, and 177 were wounded. PFC Dent was among those missing in action.

Members of the 92nd Infantry fire a mortar in this photograph from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

“We’ve identified three so far. PFC Dent would be the fourth,” Frank said. “We have a very large-scale project, dealing with unknowns in the Florence American Cemetery. So, after the war, a lot of those remains were gathered up by the Army, who went out to search for missing people. Any remains they could not identify are still buried in Florence American Cemetery in Sicily-Rome American Cemetery in Italy as unknowns. And we have a very large-scale project aimed at research to exhume those remains and identify them.”

Rows of gravestones in the Florence American Cemetery in Italy, where the remains of many unidentified soldiers lie to this day. The DPAA is still working to identify these men using DNA samples among other means. (American Battle Monuments Commission)

The DPAA has conducted thorough research as to where the remaining missing Buffalo Soldiers died.

“We’ve mapped out the battlefields. We know where men were missing. We know where men were recovered, where they are to be recovered. I think our biggest problem right now is, out of the 49 who are left, we have about ten that we do not have DNA samples from their families,” Frank said. “That slows our process down, because if we don’t have DNA to match them to, we can’t exclude them. Sometimes, excluding someone is just as good as identifying some others because it helps say that it can’t be them.”

As for PFC Dent, his family members will finally be able to honor his service.

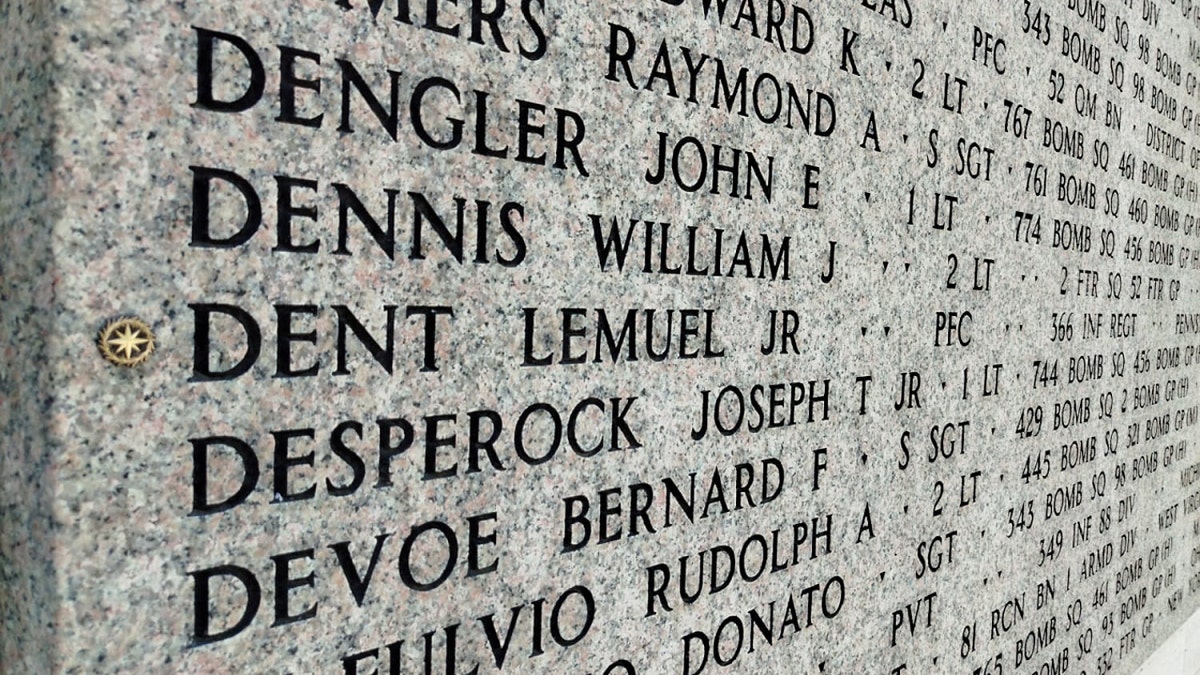

A rosette next to the name of U.S. Private First Class Lemuel Dent Jr. on a memorial for missing soldiers in the Florence American Cemetery in Italy. The rosette indicates that his remains were identified. Dent served as part of the Buffalo Soldiers of the 92nd Infantry Division during World War II. (American Battle Monuments Commission)

“That’s the whole reason that our office exists and does what we do,” Frank said. “I was a soldier myself. I think, for the most part, soldiers don’t really worry about themselves. I know when I was a soldier, my big worry was always, if something ever happens to me, how is my mom going to feel? What’s my family going to do?”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Most overseas American cemeteries list the names of soldiers who went missing in action on a memorial. For those who are eventually identified, a rosette is placed near their names. In July, a ribbon was placed by PFC Dent’s name at Florence American Cemetery.

“We’re talking about PFC Dent because the agency hit a home run. Because we made an identification. We put the same work that we put into PFC Dent, even into our strikeouts,” Frank said. “It’s very, very emotional. It’s a lot of pressure. So, when we do get an identification, of course, it feels good. But it also has to feel good enough to sustain you through the gut punch of whenever we get it wrong.”